An aerial view of the Mississippi River town Hannibal, Missouri.

According to the Fifth U.S. National Climate Assessment released in November 2023, severe weather events are increasing across the country — including flooding and longer droughts that reduce agricultural productivity and strain water systems.

It’s more important than ever for scientists and others to learn how to communicate with the public about the changing climate and environmental issues in ways that could increase support for mitigation measures.

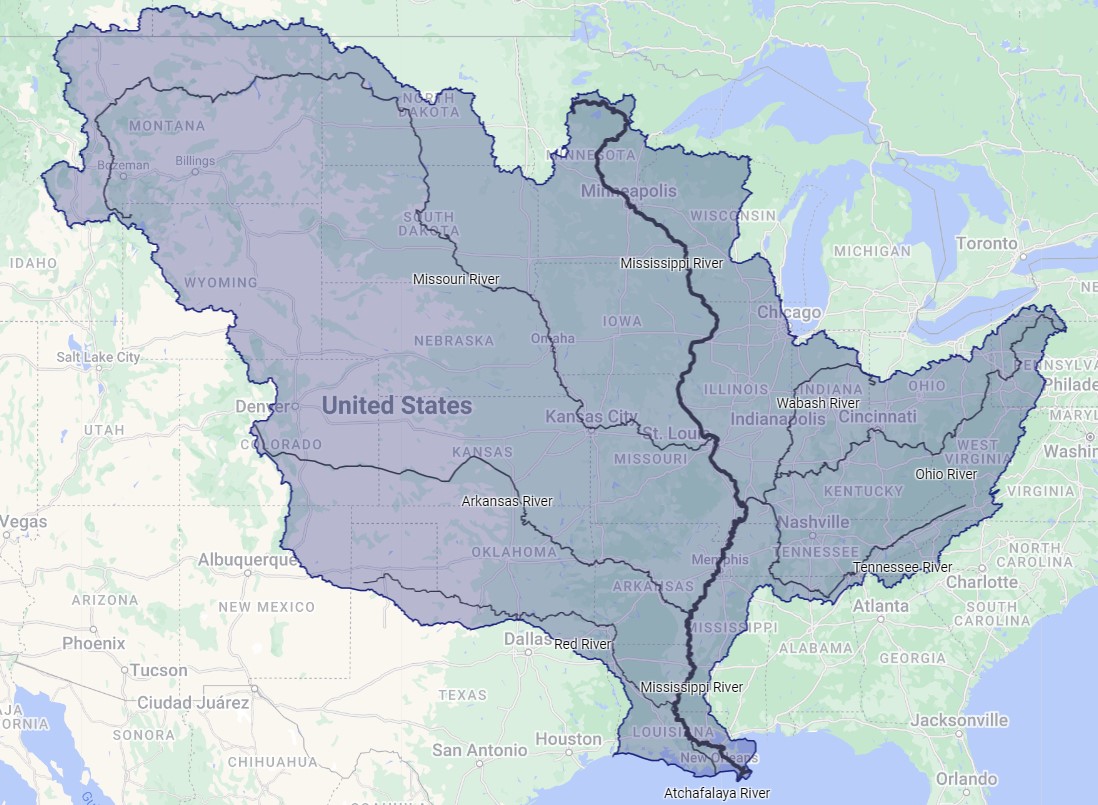

Good communicators know that the first step is to know your audience, so Kate Rose, assistant professor of journalism, conducted a survey on the attitudes and environmental awareness of people living in the Mississippi River Basin — the largest drainage basin in the United States and a vital environmental and agricultural region.

In addition to demographic questions, the survey asked respondents about their opinions on the primary cause of climate change, their trust in various sources for information about agriculture and the environment, how willing they are to participate in various climate actions and much more.

We talked to Rose about the survey and its results, her work in general, and what’s next.

Why choose the Mississippi River Region for the survey?

The survey is tied to funding related to the Mississippi River Basin Ag & Water Desk, a collaborative reporting network based at the MU School of Journalism covering agriculture, water, climate, energy and other environmental issues throughout the river basin. The goal of the desk is to enhance the impact of journalism on agriculture, water and related issues throughout the basin, which spans nearly half of the continental United States, and is relied on by millions for drinking water, commerce and recreation.

What were some interesting takeaways from the results?

There were so many insights that I can’t list here, but feel free to check out the full report. Some notable points:

• A majority of people have noticed significant changes to their state and local environments.

• Residents show strong support for sustainable agriculture methods.

• University scientists and extension agents are among the most trusted sources of science and environmental information.

• Local television remains a go-to media source.

One thing that surprised me was that a lot of people care deeply about their identity and connection to the Mississippi River, just like someone might say they’re proud to live near the Great Lakes. But on the other hand, we did find people that just really don’t understand where the borders of the basin are and whether their state was a part of it.

A map of the Mississippi River Basin from the United States Geological Survey.

When you gather all this data and compile it into a report, what’s the next step?

There’s two aspects to it. First, we hope that we’ll be able to publish some journal articles so that this work adds to the body of research on the academic side and makes a good impact there.

Second is continuing the broader impacts work. We have a lot of research at the university that’s great and can be applicable to people, but then how do you take the next step of getting it out to the public? I’ve done research around public engagement, public communication and science and I’m a huge proponent of making sure it’s done well. Universities have a major role to play in moving that forward to make better, more informed decisions in Missouri and beyond.

What have the broader impacts looked like for this survey?

We shared the results in a presentation with the journalists of the Ag & Water Desk, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources and a larger webinar that was open to the public that journalists, educators and other stakeholders attended. In addition, we’re working with MU Extension to spread the word about the survey results to those who work directly with the public all over the state. This is especially important because the survey showed that extension specialists are largely remain very trusted by the public when it comes to information about the environment.

What are you most proud of regarding this project?

I’m glad that we’ve been able to do so much on the broader impacts side and that my students have gotten a chance to get involved and give presentations. I think it’s been good experience for them.

I’ve also heard feedback that the results have validated a lot of the things journalists have encountered in their reporting, like for example, that a lot of basin residents don’t know what a watershed is. So, when journalists want to define something or include more background information in a piece, they can go to their editor, point to these findings and say, “This is a real thing, people aren’t as knowledgeable about all this as we assumed, and we need to focus on this.”

How did you become interested in this type of work?

Both my undergraduate degree and Masters are in environmental science, because I wanted to help tackle huge issues like climate change. But the more classes I took, the more I realized that people were part of that equation. And if you want to address things like climate change, it's not just understanding the science, it’s also understanding people's opinions and what motivates them to take actions. So, after I finished my master's degree, I refocused on the people side. For my PhD, I shifted my focus from environmental science to science communication broadly. I wanted to understand how people make sense of science, where they look for information, how they form knowledge, how their knowledge does or doesn't impact their attitudes. I wanted to explore all of those multifaceted connections.

What’s next for you and this project?

We are planning on doing a similar study in another year. We want to be able to ask the same questions to the same groups of people to track changes in attitudes and beliefs about these topics over time.

I’m also working on projects regarding misinformation around scientific issues — how we can help correct it or prevent it from spreading in the first place.